As a part of a recent NSF-funded CNH project (Nelson et al. 2011), The Complexities of Ecological and Social Diversity: A Long-Term Perspective*, we are exploring an idea we call “risk landscapes.” Dry farming in most of the Southwest US is a risky proposition. Partial or complete crop failures–sometimes for several years in a row–are common. Pueblo peoples traditionally mitigated this risk in part by storage and in part through the establishment of trade relationships with other groups. For these relationships to be mutually beneficial, trade partners ought to be as close as possible with the constraint that they are living in areas whose climate is anti-correlated to one’s own, so they would likely be having a good year while you are having a bad year and vice versa. This led us to investigate, for each location, where one would have to go to find a suitable trade partner.

To start, we visualize the environment in any given year in terms of a map that displays, for each point in the map, how that year’s growing season precipitation deviates from the long-term average for that point. (Our assumption is people living in these locations have developed appropriate technologies to deal with their local environments.) One such map (for 1934) is shown below.

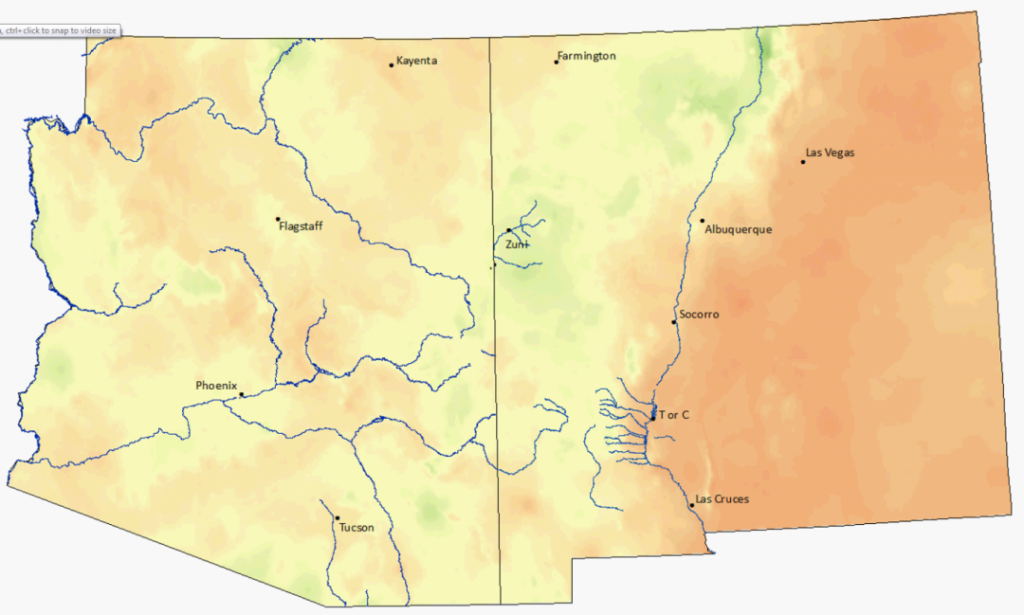

Growing Season Precipitation Deviations from the Long-term average, Arizona and New Mexico, 1934.

This map displays, for 1934, each map pixel’s deviations from that specific location’s long-term average growing season rainfall, based on high-resolution, precipitation data modeled by PRISM from the historic rainfall record. Areas shown in green are substantially wetter than usual in this year; those in yellow near average, and those in red substantially drier. Thus, in this year people living around Zuni (near the upper middle of the figure) or along the upper Rio Grande are having a relatively good year while most people living east of the Rio Grande are having a drier or much drier than usual year.

To assess the risk landscape from the standpoint of a given actor, we need to see, over the long run, what locations have precipitation deviations that are commonly anti-correlated with the location of our actor. In particular we want to know what locations would be favorable when the actor’s location is notably unfavorable, and vice versa. Locations that consistently show opposite patterns of this sort would potentially be beneficial trade partners.

We are now extending this analysis into the past using high spatial resolution temperature and precipitation data (both historic and prehistoric–derived from PaleoCAR) to assess the spatial distribution, through time of the local risk of crop failure from runoff and dry farming technologies.

Nelson, Margaret C, John Anderies, Michelle Hegmon, Jon Norberg. 2011. CNH: The Complexities of Ecological And Social Diversity: A Long-Term Perspective. National Science Foundation $1,499,551. (BCS 1113991) 9/1/2011-2/28/15

*Contact: Ann Kinzig, Arizona State University